If your picture of Thailand is cold Chang at sunset, beach bars, and the occasional “bucket” on Koh Phangan, this article might feel like it’s describing a different country.

Because rural Thailand often is!

In many villages, drinking isn’t mainly a nightlife activity. It can be a daytime routine. A social glue. A way to switch off after physical labor. Sometimes it’s as normal as stopping for iced coffee or grabbing food at the local market. And the drink that shows up again and again is Lao Khao (Thai rice whisky), cheap, widely available, and culturally familiar in a way imported spirits never really are.

That doesn’t mean everyone in rural Thailand drinks, and it doesn’t mean every drinker has a problem. But it does mean that alcohol can be woven into daily life in ways that surprise outsiders, especially foreigners who move inland, marry into Thai families, or spend time outside tourist areas. What looks like “heavy drinking” through a Western lens may be viewed locally as ordinary, even expected. And when it does slide from routine into dependency, it often happens quietly, without labels, and without much access to support.

This article is not here to judge rural communities or turn Thailand into a cautionary tale. It’s here to explain what many people don’t see, and why it exists: the role of alcohol in village social life, the economics of cheap spirits, the way habits pass through families, and the reasons help is rarely sought until things become impossible to ignore.

If you’re living in Thailand long-term, building relationships here, or simply trying to understand the country beyond the tourist version, this is one of those topics that’s uncomfortable, but important. Quiet realities usually are.

Alcohol’s Role in Rural Daily Life

To understand drinking culture in rural Thailand, it helps to step away from ideas of “leisure drinking” and look instead at function.

In many villages, alcohol is not reserved for celebrations or weekends. It often appears at the end of a workday in the fields, during construction jobs, after fishing, or while sitting together outside a house as the evening cools down. Drinking is less about escape through intoxication and more about marking the transition from work to rest, or simply passing time in a place where entertainment options are limited.

For men especially, drinking is a social activity. Sharing a bottle creates conversation, reinforces bonds, and avoids silence. Refusing a drink can feel awkward, not because abstinence is condemned, but because participation signals belonging. Saying no may raise questions: Are you sick? Are you upset? Are you distancing yourself?

Alcohol also plays a role in coping. Rural life is physically demanding, financially uncertain, and repetitive. Many people work long hours for low and unpredictable income, with few realistic paths upward. In that context, drinking becomes one of the most accessible ways to relax both body and mind. It is cheap, legal, and socially accepted. There is no barrier to entry.

What’s important to note is that this pattern doesn’t usually feel extreme to those living it. Drinking a few glasses every day may not be seen as excess if it doesn’t lead to public disruption. The line is rarely drawn at frequency. Instead, it’s drawn at loss of control. Being visibly drunk, aggressive, or unable to work is frowned upon. Drinking daily, quietly, and predictably is often not.

This distinction is where many outsiders misunderstand rural Thailand. What looks like a drinking problem from the outside may, locally, be understood as routine behavior—until the consequences become impossible to ignore.

Lao Khao and Everyday Drinking in Thai Villages

Any discussion about alcohol in rural Thailand eventually leads to Lao Khao.

Lao Khao is a clear rice whisky, usually around 35–40% alcohol, and it plays a very different role from beer or imported spirits. In villages, it isn’t viewed as something special or indulgent. It’s practical. A small amount goes a long way, it doesn’t need refrigeration, and it’s available almost everywhere—from local shops to roadside stalls.

Cost matters. A bottle of Lao Khao is often cheaper than beer and, in some areas, not much more expensive than bottled water. For people earning daily wages or irregular income, this makes it the default choice. Drinking beer regularly can feel like a luxury. Drinking Lao Khao feels ordinary.

Availability matters just as much. There are few restrictions on when or where it’s sold, and enforcement around age limits or consumption is minimal in rural areas. Alcohol is simply part of the local retail landscape. You don’t need to plan for it. You don’t need to justify it. It’s just there.

Culturally, Lao Khao is also familiar. Older generations grew up seeing it poured at family gatherings, shared after work, or offered to guests. It carries less stigma than “hard liquor” might in Western contexts. When people drink it at home, in small groups, or with meals, it blends seamlessly into daily routines.

This combination—low cost, constant availability, and cultural familiarity—is key to understanding why daily drinking in Thai villages is so common. Lao Khao doesn’t encourage moderation, but it doesn’t actively encourage excess either. It encourages regularity. And over time, regularity is often what turns habit into dependency.

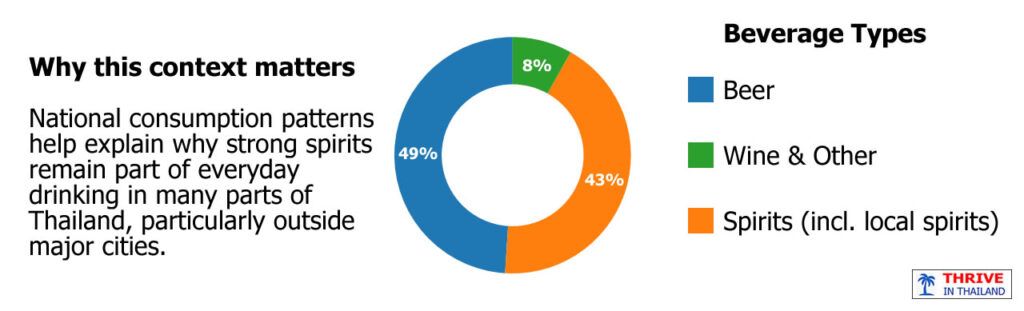

Alcohol Consumption in Thailand by Beverage Type

Available data on beverage types in Thailand helps put rural drinking patterns into perspective, especially when discussing spirits such as Lao Khao.

Source: Industry market analysis (2024/2025)

ℹ️ Beer accounts for the largest share of alcohol consumption in Thailand, while spirits, including locally produced rice whisky such as Lao Khao, make up a significant part of overall drinking nationwide.

Generational Normalization and Family Patterns

One of the reasons drinking culture in rural Thailand persists is that it is learned early and reinforced quietly.

Children grow up watching adults drink as part of everyday life. Fathers drink with uncles. Older brothers drink with cousins. By the time boys reach their late teens, drinking often feels less like a choice and more like a rite of passage. It isn’t framed as risky behavior. It’s framed as joining the adult world.

In many families, alcohol is present at meals, gatherings, and casual evenings at home. No one announces it. No one explains it. It’s simply there. Because of that, daily drinking rarely triggers concern unless it causes visible problems. The behavior itself isn’t questioned. Only the consequences are.

This is an important distinction. In rural Thai family life, the issue is not how often someone drinks. It’s whether they still work, still contribute, and still behave appropriately. As long as those conditions are met, drinking tends to remain socially invisible.

That invisibility makes change difficult. When habits are shared across generations, there’s no obvious point of comparison. If a father drank daily and still provided for his family, a son doing the same doesn’t see his behavior as different or worse. From inside the family system, it feels normal.

For outsiders, especially foreigners who marry into rural families, this can be deeply confusing. What looks like a long-term drinking problem may be understood locally as “just how things are.” Concern from outside the family can even be interpreted as misunderstanding or disrespect, rather than care.

📌 This generational acceptance doesn’t mean families are unaware of the damage alcohol can cause. It means the threshold for calling it a problem is high. Often much higher than outsiders expect.

Health and Social Consequences That Often Go Unspoken

When drinking is routine rather than exceptional, its effects tend to accumulate quietly.

In rural Thailand, health problems linked to long-term alcohol use often appear gradually. Fatigue becomes normal. Digestive issues are ignored. Chronic pain is treated with rest, massage, or more drinking rather than medical attention. Serious conditions such as liver disease or high blood pressure may go undiagnosed for years, simply because people don’t seek care unless they are unable to work.

Access plays a role. Clinics in rural areas are limited, and specialist care usually requires travel to larger towns or cities. Even when healthcare is technically available, taking time off work or spending money on transport can feel unrealistic. As a result, many people tolerate declining health for as long as possible.

The social consequences are just as understated. Alcohol-related tension inside families is often managed through silence rather than confrontation. Arguments may be written off as stress or personality issues. Financial strain caused by daily drinking is absorbed slowly, bit by bit, rather than addressed directly. Only when someone can no longer work, becomes aggressive, or creates public embarrassment does concern turn into action.

This pattern explains why alcoholism in Thailand is often discussed only at the extreme end. By the time a problem is openly acknowledged, it has usually been present for a long time. The earlier stages, where change might be easier, are rarely named or challenged.

📌 For outsiders, this can be frustrating. It may feel obvious that alcohol is contributing to health or family problems, yet no one seems willing to say it out loud. From within the community, however, raising the issue directly can feel disruptive, disrespectful, or simply pointless if no realistic solution is available.

Why Help Is Rarely Sought

In rural Thailand, the absence of support for alcohol dependency is not just a matter of limited services. It’s also about how the problem itself is understood.

Alcoholism is rarely framed as a medical or psychological condition. More often, it’s seen as a personal habit, a character trait, or something that a person should manage on their own. Seeking help can be interpreted as admitting weakness rather than addressing an illness. In communities where self-reliance and endurance are valued, this creates a strong barrier to intervention.

Practical obstacles reinforce this mindset. Formal treatment options for alcohol dependency are scarce outside major cities. Rehabilitation centers, counseling services, and long-term support programs are largely inaccessible to rural populations. Even when people are aware that help exists, reaching it may require money, travel, and time away from work, all of which feel out of reach.

Instead, informal systems step in. Temples sometimes offer temporary refuge for people trying to stop drinking, providing structure, routine, and distance from daily triggers. Family members may attempt to control access to alcohol or apply pressure through shame or obligation. These approaches can help in the short term, but they rarely address underlying dependency.

Another factor is stigma, but not in the way outsiders often expect. Drinking itself carries little shame. Needing help does. This inversion makes early intervention unlikely. As long as someone continues to function, even poorly, the expectation is that they will eventually correct themselves.

📌 Understanding this helps explain why daily drinking in Thai villages can persist for decades without formal intervention. The system isn’t indifferent. It’s simply not designed to treat alcohol use as something that requires structured support.

How This Reality Affects Expats and Mixed Families

For foreigners who live in rural Thailand or marry into Thai families, drinking culture can become one of the most difficult realities to navigate—not because it is hidden, but because it is so openly accepted.

Many expats arrive with clear ideas about alcohol use shaped by their own cultural background. Daily drinking is often associated with dependency, and concern is expressed early. In rural Thai settings, that concern may be met with confusion or dismissal. What looks like a problem to an outsider may be seen locally as normal behavior that only becomes an issue under extreme circumstances.

This difference in perception can create tension inside mixed families. A foreign partner may worry about health, finances, or long-term stability, while Thai relatives see no urgent reason to intervene. Attempts to raise the issue directly can backfire, coming across as criticism of family norms rather than care for an individual.

Financial strain is another common source of frustration. Regular spending on alcohol may feel irresponsible to someone used to tighter budgeting, especially when money is already limited. Yet because the amounts are small and spread out over time, the impact often goes unacknowledged until debt or hardship becomes visible.

Over time, some expats adjust by lowering expectations. Others withdraw emotionally from the issue altogether, accepting that this is an area where change is unlikely. A few attempt to push for change, usually with mixed results. What’s important to understand is that none of these responses are about indifference. They’re about navigating a cultural gap where concern, responsibility, and normal behavior are defined very differently.

What’s Changing (Slowly and Unevenly)

Drinking culture in rural Thailand is not static, but change happens gradually and inconsistently.

Younger generations in some areas are drinking less than their parents, especially where education levels are higher or where people migrate to cities for work. Exposure to urban lifestyles, health information, and different social norms does influence behavior. In those cases, daily drinking becomes less automatic and more situational.

There have also been public health campaigns aimed at reducing alcohol consumption, particularly around road safety, drunk driving, and domestic violence. These efforts have had some impact, but they tend to focus on visible harm rather than long-term dependency. In rural settings, where drinking is mostly private and habitual, such campaigns rarely change daily routines.

Economic pressure cuts both ways. Rising prices and unstable income can reduce spending on alcohol for some households. For others, stress and uncertainty reinforce the habit. As long as Lao Khao remains cheap and widely available, it continues to be the easiest option for coping and socializing.

What has not changed significantly is access to structured support. Outside major cities, treatment options remain limited, and community-level approaches still rely heavily on family and informal systems. Without better alternatives, expectations around self-control and endurance remain the default response.

📌 Taken together, these shifts suggest that drinking culture in rural Thailand is evolving, but slowly. The patterns described in this article are not disappearing. They are being reshaped unevenly, depending on location, opportunity, and exposure to different ways of living.

Closing Thoughts

Drinking culture in rural Thailand is not easily reduced to labels or statistics. It exists at the intersection of habit, availability, social connection, and economic reality. What may look like a clear problem from the outside is often experienced locally as routine, familiar, and deeply woven into daily life.

Understanding this doesn’t mean excusing the harm alcohol can cause. It means recognizing why change is difficult, why concern is often expressed late, and why simple solutions rarely work. For anyone living in Thailand long-term, especially outside urban centers, this is one of those realities that becomes clearer with time, patience, and proximity.

📌 Like many aspects of rural life, it’s quiet, complex, and rarely discussed openly—but understanding it helps make sense of the country beyond the surface.

💬 If you’ve spent time living outside Thailand’s cities, your perspective matters — feel free to share your observations or experiences in the comments.